Choosing Goals (How to Figure Out What You Want)

Prompts to help you choose which goal to pursue.

The obvious question once you understand the importance of goal setting is “OK, so how do I figure out what I want?”.

In this chapter, I will share a few prompts and exercises which I have found useful. As with any question, the more you can diversify your avenues of attack, the better your final answer will be.

The first step is to generate a list of goals to choose from. Before you decide what to pursue, list out all your possibilities. Goal setting is your opportunity to write your own story . . . give yourself permission to think big. Practicality is not your friend at this stage. Leave all notions of “should” or what “makes sense” aside for now.

A few prompts to help you get started:

What is the most important problem that you could act on right now?

What issue or cause would you want to work on but people say is “too big” to tackle?

In 2043, you’re giving a keynote at TED: what is the topic of your speech?

What do you want your obituary to say? [Write it out!]

What would you do if money were no object?

If you were the last person on Earth, what would you do?

This long-term focus shifts our search area from what brings us happiness to what will give our life meaning. We are notoriously bad at predicting what will make ourselves happy and most of our happiness is actually genetically determined, anchored to a set point.

Meaning is much easier to get a handle on than happiness. We derive meaning in our lives from the pursuit of a challenging and worthwhile goal. The emphasis here is on “pursuit”, the achievement of a goal is relatively inconsequential from the amount of meaning we derive from it. I suspect that much our existential angst comes from confusing happiness with meaning as goal pursuit leads to inevitable fluctuations in happiness.

This model of emphasizing pursuit over achievement anchors two of my favorite prompts for choosing goals, using the powerful technique of inversion:

“What would you never regret attempting, even if you failed?”

“What could you do to ensure that you live an unsatisfying life?

When deciding what you want, try imagining what your ideal day would look like. How do you want to spend your time? Where, and with whom?

Write out the script of a perfect day. Visualize and practice the important elements so that the script eventually becomes second nature — that performing one activity activates associations of what a perfect day feels like. How are your days different now? To shift the trajectory of your life, commit to taking one tiny step towards the realization of your perfect day, every day.

Time is the ultimate equalizer. No matter who you are, everyone gets the same 168 hours in the week. Where are your 168 hours going now? How intentional are you about planning out your upcoming week? To add anything new, something needs to be replaced. Most people think “being productive” means working more. In reality, the most productive people usually work fewer total hours — they just focus on the right things.

Do you regularly reflect on which activities are low/high value? You create pockets of time by effectively using it. Do you have a process for arbitraging your time – replacing low value activities with high value ones? Define what “time well spent” means to you and regularly track how much of your time actually falls within that category.

Knowing how you want to spend your days creates an exciting menu of available goals to tackle. This understanding requires regularly consciously revisiting your deepest values while attempting to immunize yourself from cultural and social expectations.

Also, consider how much money you really need to create the life you want, beyond status-seeking score-keeping? [Not sure? Check out the Dreamline Exercise.] Sometimes two values can conflict and concurrent pursuits yield fruitless. For example, prioritizing lifelong friendships might conflict with also prioritizing a life of travel and adventure.

So, do you want to be:

Spending your days building, creating or amplifying the work of others?

Collaborating closely or doing your own thing?

Living in public or making it happen behind the scenes?

Blurring the distinction between work and play or focusing on balance and creating the life you want?

An important meta-skill to build for goal setting is your ability to take the outside view. Ever notice that when our friends struggle, we clearly see the next steps they should take, but they can’t see them? You’re not immune. We have difficulty stepping outside of our experiences to view ourselves objectively. Our entire lives have been filtered through the lens of our own narrative interpretation, creating a persistent blind spot when we turn our gaze inward. You could even say that the true goal of learning in the modern era is to shine a light upon our previously invalidated assumptions.

The following exercises will help you take the outside view on your own life:

Imagine you have just been transported into your body. You have amnesia so all of your past decisions are unknown to you. Your only option is to appraise your current situation and make the most of your inherited skills and knowledge. What would you do next?

Pretend you are the protagonist in a novel you’re reading. Fill in the blank: “why don’t they just do ______ already?”

Now that you have generated some potential goals, let’s narrow down the list.

First, cross off any goals designed to meet the expectations of others. Your entire life is a creation of your choices. While others may influence your decisions, only you can physically take a step forward. Our posture towards goals should reflect that freedom of choice.

Do not relinquish or take for granted your ability to choose. In our single-player games, fulfillment comes from following our own inner scorecard. Every goal should be of your own choosing and for your own reasons.

Second, differentiate your goals from your dreams. While pursuit of a goal is inherently rewarding no matter the result, dreams depend upon achievement.

Identify your instrumental goals: these are the intermediate steps on the path towards achieving your larger goal. Study the nature of what you are signing up for. Anything resonating with your life’s meaning will need to be practiced regularly. Is this realistic for you?

Every choice comes with a corresponding opportunity cost. What would you need to sacrifice to pursue this goal? Does the goal still excite you after you’ve recognized the price you will have to pay for its achievement? If you want to be a rock star but are unwilling to spend your days practicing your craft, “becoming a musician” is not a goal but a dream.

Now that you have a list of potential goals, how do you choose between them? With limited space on our metaphorical plates, what items from the buffet do we choose?

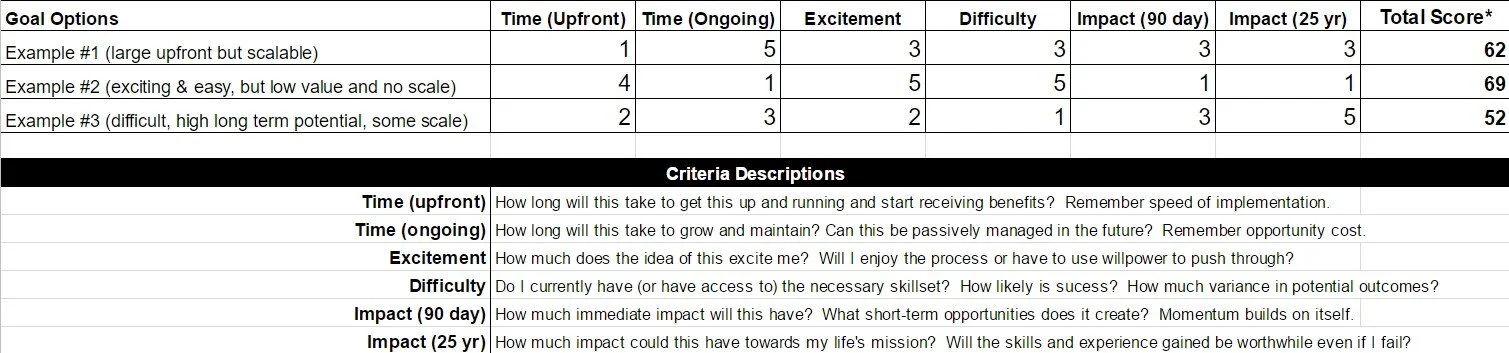

I find the following exercise very helpful for making tough decisions. It results in an expected value for each goal, an objective score far superior to making apples-to-oranges type comparisons in your head. I have used modified versions of this exercise [try it!] for many of my major life and business decisions such as career changes, moving to a new city, or choosing my next project to focus on.

I start by listing out the criteria I will use to evaluate my options, limited to a maximum of the most critical 5 or 6 factors. For goals, my critical factors are Time Investment, Enjoyment, Difficulty, and Potential Impact. Simply put, an ideal goal will be both exciting and impactful but not too difficult or time-consuming. I rate each goal from 1 to 5 for each factor. To get a final score, I weight the factor ratings exponentially (rating ^ 2) and add them up.

My final scores always surprise me, revealing hidden biases or a previous over-weighting of trivial factors. You’ll find that the majority of options are easily dominated by others and can be easily removed. With multiple remaining contenders, I will then play around with ratings or weightings to hone in on the crux of the decision.

The true power of this exercise comes not from the final score but in the forcing function of 1) deciding which criteria are most important and 2) questioning underlying assumptions. Consider this exercise a guide to harvesting your subconscious; accurate but possible to overwrite.

If stuck between two options, here are three rules of thumb to break the tie:

I never choose the status quo unless it is the overwhelming favorite. We are far too cautious towards making big decisions. People who make a change generally report being substantially happier than those who do not.

I choose whichever goal is the most intimidating. The Resistance, usually manifested as fear or doubt, tries to get us to justify the easier path. These emotions self-sabotage us in an attempt to protect our ego and need to be corrected for.

I choose whichever goal can be completed the fastest. Every goal in progress has an associated carrying cost and every goal achieved builds a platform to pursue more challenging goals in the future. If you are starting out, build momentum by optimizing for completion. It’s very easy to turn a successful small project into a larger endeavor but falling short repeatedly is a recipe for disaster.

If your next move is still not obvious, see if you can test the assumptions these scores draw upon. This could mean doing further research, talking to others who have done similar work, or conducting a brief experiment of your own.

Due to imperfect self-knowledge, it is extremely rare to choose the right goal the first time around. That’s OK. Goal setting is an iterative process and your aim becomes more true with each attempt. Think of your current goals as a rough draft which represents a tentative direction to head toward.

If you’re waiting until you have all the information, you’re waiting too long. The world is full of unknown unknowns, revealed only through experience. Attempts to make progress through deliberate practice will bring you a more accurate map of the territory than any prompt or exercise. As Eisenhower said, plans become useless, but planning is indispensable. Optimize for decision speed as you can only course correct once you’ve starting moving forward.

In the next chapter, I will show you how to optimally define and frame your goals to maximize your likelihood of achieving them.